Beautiful doesn’t have to mean high maintenance.

Think of the number one goal you have for your outdoor living space. I’m willing to bet at least one of the top 5 is low maintenance. If you’re like me, you just don’t have the time to do everything on your ‘to do’ list. Sometimes necessary things like keeping your landscape alive don’t even make it on the list until it’s too late.

I get it. You’re busy. You could think of 10 better things to do than standing in your yard with a garden hose watering your pansies.

I get it. You’re busy. You could think of 10 better things to do than standing in your yard with a garden hose watering your pansies.

But what about a sprinkler, on a timer or a full-on irrigation system? May be a good call, as long as you’re not on watering restrictions when you need it most, and as long as the water going through it is not hurting your plants.

“I love tap water,” said no plant ever.

True. Hard or chlorinated water is better than none at all, but if given a choice most plants will choose rainwater every time, even if it’s not falling from the sky. Why?

- It’s naturally soft. Some minerals are good, but too much can really hurt your plants. Water softeners actually add salt, which is notsogood either..

- It’s slightly acidic. This means it helps keep the soil at the optimum pH so nutrients are available to plants, at least according to Leonard Perry, Extension Professor at University of Vermont…

“Soil pH is important because it influences several soil factors affecting plant growth, such as (1) soil bacteria, (2) nutrient leaching, (3) nutrient availability, (4) toxic elements, and (5) soil structure. Bacterial activity that releases nitrogen from organic matter and certain fertilizers is particularly affected by soil pH, because bacteria operate best in the pH range of 5.5 to 7.0. Plant nutrients leach out of soils with a pH below 5.0 much more rapidly than from soils with values between 5.0 and 7.5. Plant nutrients are generally most available to plants in the pH range 5.5 to 6.5. Aluminum may become toxic to plant growth in certain soils with a pH below 5.0. The structure of the soil, especially of clay, is affected by pH. In the optimum pH range (5.5 to 7.0) clay soils are granular and are easily worked, whereas if the soil pH is either extremely acid or extremely alkaline, clays tend to become sticky and hard to cultivate.” – University of Vermont Extension – Dept. of Plant and Soil Science (http://pss.uvm.edu/ppp/pubs/oh34.htm)

So if you live where there are never droughts or heavy rains, you’re all good. Stop reading now.

So if you live where there are never droughts or heavy rains, you’re all good. Stop reading now.

Everyone else, read on.

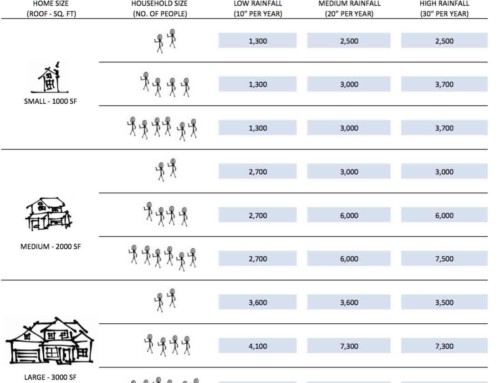

Saving rainwater is not just for dry climates, but it can really save money when you add the cost of plants that otherwise cannot be watered due to watering bans. Restrictions don’t apply to harvested rainwater, so the more you can catch and store, the more you can protect yourself and your gardens. It’s worth a mention of the underlying reason for all this “low maintenance” buzz. We are strapped for either time or money, or both. Let’s be honest. If you really have more money than you need, you can just pay others to do the maintenance.

that’s a big hole in the ground

And if you can reduce your taxes that pay for massive infrastructure projects, by avoiding the need for as many in the future, you can gain a little more time and money by not being surprised by “necessary” tax hikes. If you live in a high-rainfall area, you also benefit from slowing down some of the massive amounts of runoff from all the developed, solid surfaces. Huge municipal projects to handle this include the 1.4 billion dollar “Big Pipe” in Portland and the billion dollar “Deep Tunnel” in Milwaukee. These engineering wonders, while effective at what they do, need to be paid for by higher rates and may eventually reach maximum capacity, requiring even more massive projects and water rate hikes.

Really Big Band-Aids

“Echo!.. echo… echo…”

let’s dig a little deeper, boys!

And what are these big engineering solutions really doing? Getting water away from the “problem areas” to prevent flooding, right? Oh sure, but not necessarily back into the ground, where it should be going in order to replenish the supply drawn out from wells. These solutions are handling the effect of the problem like some drugs only help cope with the symptoms, but what is the cause, and is there even a cure? Can we do anything to filter this water and reuse it, without being washed away by the flood? Wastewater treatment facilities like Milwaukee’s and L.A.’s have come a long way in treating and filtering sewer water to the point of drinkability, but what about stormwater? Currently when it falls, it cleans up the streets nicely but picks up all those pollutants along the way and dumps them directly into our lakes and streams. This not only causes water pollution and excessive algae blooms, it does nothing to replenish the supply.

What Does This Have to do With Your Low Maintenance Landscape?

Directly: Nothing. Indirectly: Everything. Catching rain not only reduces your own water bill and helps your plants. When a bunch of people do it, the effects really add up. Cities that are dependent on aquifers and groundwater will see more of an impact, although lower groundwater actually lowers water levels in lakes and streams, too. Even though they sit right next to the Great Lakes, Milwaukee and Chicago currently have groundwater drawdowns of about 500’ to 1000’ below original pre-European settlement levels, respectively.

You, to the Rescue!

Smaller scale individual solutions, when added up, can help to avoid more water hikes, offset the effects of drought and heavy rains and also reverse or lessen the groundwater drawdown that is reaching critical levels.

Aside from all this “greater good” stuff, what’s really in it for you?

Sometimes it’s hard to do something for the environment or the future if it costs you more right now. In your day-to-day life, the bottom line boils down to your payback, your return on investment. How immediately can you expect to see a benefit from your own personal investment in a rain collection system?

The Benefit

And so we come back to your own backyard, and your own pocketbook, and your own time clock. Whether you have more time than money or more money than time — or for most of us at some point in our lives, not much of either one, what you need is a way to provide a place to escape once in awhile, relax, enjoy a little nature. To stop and smell the roses. You shouldn’t need to constantly worry about keeping those roses alive, fighting a losing battle to get the right soil, nutrients, water. That kind of defeats the purpose of having them

And so we come back to your own backyard, and your own pocketbook, and your own time clock. Whether you have more time than money or more money than time — or for most of us at some point in our lives, not much of either one, what you need is a way to provide a place to escape once in awhile, relax, enjoy a little nature. To stop and smell the roses. You shouldn’t need to constantly worry about keeping those roses alive, fighting a losing battle to get the right soil, nutrients, water. That kind of defeats the purpose of having them

Have a green thumb, or at least let them think you do.

Have a green thumb, or at least let them think you do.

Small details make a big difference.

Have you ever tried so hard to take care of a plant, only to watch it slowly wither and die? That’s discouraging, I know. I’ve done it. What if watering your plants with exactly the right amount, with the wrong water, is actually killing them? What if you even had the time to monitor soil nutrients, adding fertilizers, only to find (or to be completely baffled by not knowing) that your high soil pH is preventing the plants from getting them? When you do figure it out, you could constantly add soil sulphur to counter this, and spend more money on peat, pine needle mulch, and also consistently flush the soil to dilute the accumulated salt from artificially softened water (but wait, what are you flushing it with?)… You could get a reverse osmosis filter and water your plants with pure drinking water… You could buy bottled water and really flush your money down the drain…  Or, you could catch and store all of the flood that comes out your downspouts and runs off down the street every time it rains. You could even do it now without lining up the barrels or tanks, or destroying the landscape you’re trying to save to bury a cistern. Then just make it automatically water your plants for you, and… You would be one step closer to a more beautiful, low maintenance landscape.

Or, you could catch and store all of the flood that comes out your downspouts and runs off down the street every time it rains. You could even do it now without lining up the barrels or tanks, or destroying the landscape you’re trying to save to bury a cistern. Then just make it automatically water your plants for you, and… You would be one step closer to a more beautiful, low maintenance landscape.

Now that everything is growing like mad, what about all the weeds?!

Of course, I can’t talk about a “low maintenance landscape” and not talk about weeds! Alrighty then, here we go..

The gravel garden

Backing up for a minute, a way around the entire watering conundrum is planting really drought tolerant plants, in their native environment. Natives have, after all, adapted to whatever climate and soils they are native to– without our help. One thing I see regularly around new house construction is covering all planting beds with a fabric weed barrier and stone mulch on top. What this creates is deferred high maintenance, and another thing I see regularly is around 10 to 15 year old stone mulch on “weed barrier” producing as many weeds as if the stone had never been installed. Problem with weed barrier is that it is also any-plant-barrier, and a pretty good rainfall barrier, so you need to cut through it so your plants can grow… along with, you guessed it: weeds.

Courtesy of Wisconsin Public Radio, Larry Meiller Show, horticulturist Jeff EppingOne solution to the weed barrier problem, if you just really want to use that gravel pile you’ve been hoarding, is a fairly new idea of a deep-gravel garden. Here is a great little write-up on it covered by the Larry Meiller Show interviewing Jeff Epping, director of horticulture at Olbrich Botanical Gardens in Madison: http://www.wpr.org/gravel-gardens-are-low-maintenance-drought-resistant-horticulture-expert-says Still, this is at an even greater initial cost for the 4-5 inches thick gravel. And it also still leads to the ongoing annual maintenance of any stone mulch planting to remove all organic matter that allows weeds to start.

Besides the planting medium, Epping said that there’s other organic material to watch out for that should stay out of the gravel — for example, spent foliage from the previous season. While staff at Olbrich like to leave the plants up through the winter for visual interest, they are careful to cut the plants back to the gravel level and clear it all out first thing in the spring. Rakes and blowers are both useful tools for getting rid of every shred of organic matter that might get caught in the gravel.

There’s just no getting around some kind of maintenance. Just need to pick your battles, and your weapon.

The carpet garden

Similar to the plants used in rooftop gardening, this is a technique of using a variety of low growing groundcover plants, usually also drought tolerant, to create works of art with plants in small spaces or areas. You can cover larger areas, too. Then just use larger sections to cover, and call it a “lawn alternative.”

Stephanie has a bunch of great examples over at Garden Therapy on this page: http://gardentherapy.ca/carpet-gardening-with-groundcovers/

The Hybrid – Overplanted Underplanting

What? I don’t mean underplanting as in, few and far between. On the contrary, underplantings will fill in better the closer together you plant them. In this case, the underplanted groundcovers do exactly what groundcovers do: fill in to choke out weeds and reduce the need for annual mulching, oh, and look good when in the right location.  Examples? One of my favorite groundcovers for this here in the Midwest is ajuga. There are a bunch of different varieties and shades, of which most have a darkish purple metallic color and beautiful blue flowers in May/ June. They tolerate a wide range of zones, sun/ shade, and soils, preferring acidic soil with a pH range of 3.7 to 6.5. (http://www.thegardenhelper.com/ajuga.html) Did you catch that? A soil pH of 3.7 to 6.5. I’m not sure, but given what we just learned about soil pH, they might benefit from being irrigated with harvested rainwater. Others include: For sun: Sedum ‘Lemon Ball’, acre (stonecrop), ‘Voodoo’ (red), Thyme ‘Pink chintz’, woolly thyme, lysimachia (ok they say it’s invasive but I have not found it to be so much, and it’s pretty), persecaria ‘Dimity’ (this was called polygonum ‘affine’ when I first met it – names change), dianthus ‘zing’ For shade: Ajuga (also takes some sun), lamium, vinca (will take over), pachysandra, tiarella (love it), sweet woodruff (gallium) and wild ginger (asarum).

Examples? One of my favorite groundcovers for this here in the Midwest is ajuga. There are a bunch of different varieties and shades, of which most have a darkish purple metallic color and beautiful blue flowers in May/ June. They tolerate a wide range of zones, sun/ shade, and soils, preferring acidic soil with a pH range of 3.7 to 6.5. (http://www.thegardenhelper.com/ajuga.html) Did you catch that? A soil pH of 3.7 to 6.5. I’m not sure, but given what we just learned about soil pH, they might benefit from being irrigated with harvested rainwater. Others include: For sun: Sedum ‘Lemon Ball’, acre (stonecrop), ‘Voodoo’ (red), Thyme ‘Pink chintz’, woolly thyme, lysimachia (ok they say it’s invasive but I have not found it to be so much, and it’s pretty), persecaria ‘Dimity’ (this was called polygonum ‘affine’ when I first met it – names change), dianthus ‘zing’ For shade: Ajuga (also takes some sun), lamium, vinca (will take over), pachysandra, tiarella (love it), sweet woodruff (gallium) and wild ginger (asarum).

Leave A Comment